august 19, 2011 — 10:16 a.m.

Teen Vogue has this contest on Figment, a previously ambitious NYC-based social media platform for young writers. The contest is about “Fashionweek.”

After enduring several contests revolving around inherently late millennial, YA topics like “steampunk” and “The Hunger Games” and “Vampires” and “first crushes,” I figure this is something that I can passionately write about. After all, I have a “past” when it comes to this sort of thing.

I kill myself getting my piece down to the word count. I enter. I get a few “hearts” from people who know me, but not quite enough to make it into the finals to get read by the editors at Teen Vogue. I am annoyed when I find out a month later that the winner is some high school girl from the Midwest. Evidently, she has a ton of friends and an instinctual dedication to pandering, all too pleasantly, to the judges.

I’ve got to give her credit.

She is likely as miserably insecure as me, but she either innately understands how to work the system, or a parent, teacher, or paid consultant has coached her in the ways of the young adult lit biz. She keeps it trite, trendy, and triumphal. Her story gets about double the amount of hearts as the other entries. I admire that in her. And, I get really angry with myself.

“Why can’t I try harder to get my work out there? Why don’t I have enough friends? Why doesn’t anyone really like me?” I bleat to myself, as I read the “winner’s” entry about a teenage model whose mother used to read Vogue to her as nightly bedtime stories…and now, lucky girl, she’s about to head down a catwalk at Fashionweek.

Of course I am hating myself even more because the story makes almost no sense at all. Seriously. What could the teenymodel’s mother actually have read to her from Vogue when she was a six-year-old baby princess? Would she skip over the super-thrilling accounts of a former supermodel’s Brazilian waxing in the incredibly capable hands of Dominga, a dazzling escapee of that infamous Argentinian prison for drag queens, the horror stories of Botox injections gone bad in Guadalajara, Seoul, or some private Island not far from Rio——and to get straight to the confessionals——especially Hollywood’s battles with anorexia, substance abuse, and/or PTSD/depression triggered by the relentless sexual abuse of the studio bosses, producers, writers, directors, and oligarchs dominating The Industry.

“WHERE IS THE LOGIC TO THIS STORY?” I scream to myself.

Then, I realize what an idiot I am. This whole contest is meant to promote the “Vogue” brand. Her story is perfect for their purposes. It’s nonsensical. But, isn’t the whole idea of a “Teen Vogue” slightly warped to begin with?

I decide to rewrite the piece and post it to fb.

Fear of Fashion

In Western society, there are “perks” to being relatively tall, fairly pretty, and extremely thin. It may be unfortunate, but it’s true. And, of course, there are even more perks associated with holding great wealth. And, there are still more perks associated with owning even just a modicum of fame. And, while I might not always enjoy many of these perks, I recognize the power associated with having them.

I am taller and far too thin. While I am pretty enough to be noticed, I am certainly not dazzling enough, not perfect enough, to be paid as a professional visage. And, while I hail from a lineage of great wealth, the most important numerals were long ago lost to a mottled morass of drunken gambling, multifarious all-too-expensive affairs, and a seemingly endless river of bad investments.

Multiply the aforementioned financial flaws by an unquenchable, sociopathic craving for luxury goods, primarily, in the form of my grandfather’s insatiable addiction to single malt scotch, exotic automobiles, real estate, and model/actress/whatevers, and the scale of our family’s squandered opportunity soon becomes apparent. Sadly, my mother’s even more craven obsession to fine leather goods, silks, spas, and European prêt-à-porter, and seedy hedge fund managers, eviscerated the remaining numerators. Considering mother’s extraordinary birthright, this is a truly horrible shame.

Alas, mother was, and to a certain extent, remains, a quintessentially luminous, post-modern Edie Sedgwick. Well-spoken, polished, radiant––and as silver-tongued as she is sociopathic––when mother walks into a room, people whisper. Air kisses, bear hugs, and the occasional toasts-to-end-all-toasts, greet mother at almost every gathering of the fashion/theatre/film élite. Moreover, despite the ravages of a frightfully failed early marriage, a horrifyingly abusive, sycophantic, long-term live-in association with vile, felonious financier, she retains her figure, her miens, and her wit.

Mother is neither publicly strung-out, nor seriously over-the-top in any of her civic appearances. And, because her name still carries with it the aura of relatively old money, the social powers-that-be incessantly ensure she remains “on the list”—–even when the real insiders know for certain that she might be just a little bit of a fraud. Of course, there are those who might suppose that the power of her personal “brand” has outlived the goodness of her “product,” (much like the fashion house that continues to sell its “licensed” goods extremely well, even no one would ever be caught dead in its couture collection, if such collections continued to exist). The fact remains: her name is a “name.” However off-key it might be, in a society that celebrates notoriety over accomplishment, her name still opens doors.

Mother’s modeling career might have been brief——far too brief to have ended up on the cover of Greek Elle, let alone Spanish Vogue——she made just enough of an impact before her career ending fight(s) with Gilles, Gérald, and Eileen, that when combined with her colorful lineage, she still knows just about everybody who is anybody in New York, Miami, Paris, Hollywood, and Cannes.

Thus, my “pseudo-celebrity” (or more correctly, “near-not-quite-almost-pseudo-celebrity”) is, of course, not entirely of my own making. However, it is, for the most part, at this point in my 21-year-old life, my only inheritance, save for an over-leveraged apartment in a “good” building on Central Park West. Indeed, I have not earned “it” on my own, as of yet anyway.

But, the question of whether my celebrity is “near-celebrity” or just “pseudo-celebrity” is not the issue at hand. The concern is, quite simply, the potential access I enjoy to the perks all-too-often associated with height, fitness, beauty, wealth, and “fame.” And, unfortunately, without much more than the tiniest hint of arrogance in my voice, I must admit that despite my relatively low status among the global elite actually possessing of the above attributes, I still often enjoy a great deal of the privileges afforded to those of good bones, good breeding, good fortune, and good timing.

On the basis of some oddly perceived historical importance, I all-too-often receive invitations to the openings and gatherings, fundraisers and weddings, galas and teas, dinners and previews, lunches, brunches, and rendezvouses of those who enjoy actual importance and social standing. Mother receives all of the aforementioned, multiplied by a factor of four.

Regardless of the significant variations in actual status attributed to her negatively fluctuating net worth, mother is, quite simply, one of those women who must be invited.

When and if she actually arrives, mother is greeted with such an extraordinary affection, I am usually left to wonder: “How it is possible that she can be so exceptionally lonely, cruel, and self-loathing in private, yet so fabulously joyous, entertaining, and utterly engaging in public?” It is as if the myriad transgressions, indiscretions, and follies of her private life are judiciously occluded by an extraordinary public visage, a glimmering chimera of glamour so profoundly fabulous that it completely obscures the reality of her actual social standing.

Thus, understood from this context of hyperbolic morass of social puffery and maybe even deceit, Fashion Week has come to illustrate one of my deepest personal tensions. It is, simultaneously, one those fabulously glamorous social perks I used to adore, but it is also one which have come to dread with venomous internal resolve.

In so many ways, this is incredibly and painfully unfortunate. For the first fifteen years of my life, I was enthralled, entranced, and enchanted by every detail associated with the events of Bryant Park and the subsequent gatherings surrounding “The Week.” Indeed, I was quite often as omnipresent at gatherings of the fashion élite as a Prada bag, Manolo Blahnik pumps, or depending on the season, enormous Chanel shades. As an infant, a toddler, and a schoolgirl, I served as both Mother’s companion and her penultimate accessory.

At first, I was a novelty. I was the “Isn’t she so cute (fabulous, adorable, belle, bella, gorgeous, fav-u-lous), dah-ling?” bauble meant to draw attention away from the lines quietly burrowing into Mother’s taught, angry, all-too-experienced skin.

Then, as I aged into my early tweens, I became more of a budding-fashionista-prodigy. My “ever-so-astute” commentary started enough conversations that the issues of Mother’s painful break-ups and financial crises would hardly ever be broached.

While I now view frivolous remarks such as, “The intensity of this season’s Galiano collection has been eclipsed by McQueen’s unquenchable devotion to subjugation of traditional femininity…” as complete and utter drivel, I have come to understand how the curious dichotomy of such commentary emanating from an energetic young womyn of nine, ten, or eleven, might present a pleasantly brief diversion to the designers, writers, and socialites seeking respite from the attention-seeking human pestilence clustered about them.

Yes. Those years, from the early 90s to the mid-2000s were a fanciful time. They were a time in which fantasy and reality merged as one during Fashion Week and other similarly grand public events.

I was no longer merely a daughter. I was a companion, a confidante, and a friend. During our many public appearances, I was my Mother’s equal. Better still, she knew it and it mattered not. It was part of her grand design. I was an elaborate lure––a decoy strategically positioned to draw all but the most innocuous attention from Mother, lest the world discover the seething rot beneath her highly polished façade. Worse, I knew that I was her accomplice in this ruse. And, worse still, for a long time, I not only accepted it, I reveled in the attention.

But, none of this came without a cost. It was all a grand deception. Beneath the faux glamour displayed by mother, beneath the layers of leather, and wool, and iridescent silk, brewed an insidious disease, a despair––a deeply destructive desperation born of too many decades lost to drinking, drugs, and anorexia.

For Mother, anorexia was, and is, as much of a lifestyle as it is a disease. In fact, she still refuses to admit she has a problem. For Mother, anorexia is not a disease, it’s simply a diet plan. Worse, she’s been on the cappuccino/cigarette diet since the 80s and because her constitution is so strong, she never seems get the health problems that usually accompany anorexia, the disease. In all likelihood, however, she probably has problems ranging from osteoporosis to hypokalemia, but her drug use, anger, and extraordinary willpower mask most of the side effects so well that, to the average fashionista, she simply looks incredibly “fit for her age.”

Thus, I never learned to the disease as a “disease,” I only saw the emotional pain of endless bad relationships, mental illness, financial loss, and familial self-destruction.

Over time, dealing with her inner pain became my own special affliction. It eroded my strength. It sucked the soul from my bones. It ripped my heart into tiny bits of broken flesh. Beyond ballet, “restriction” (anorexia) became my only form of true control.

I might not have been able to control Mother’s rage, her depression, her anxiety, or her lack of true affection, but I could control what I ate or didn’t eat.

I might not have been able to control what “others” did to me as I lay in bed from three to five a.m., but I could always control what I did or did not eat.

It was easy. Since she rarely ate regular meals, whether I ate, or not, was solely up to me. As far back as I can remember, unless we went out for dinner, whether I ate or not was left almost entirely to my sole discretion. If I was hungry, I would either find something to consume from our consistently sparse Sub Zero refrigerator, order a trifle from the bodega, or have something delivered from the Chinese restaurant three blocks away.

During the times that we lived with “he who shall remain nameless,” my longing for “control” through restriction and the pain of far too much ballet spun out of “control.“

Anorexia became both my destroyer and my destroy-her. What began as my only real “control” in life, the tiniest, most miniscule source of “control,” became all-consuming, all-defining, weapon to use against my enemies, my inner demons, my mother, and myself. And, the more I used this samurai sword of self-abuse to achieve ever-greater control and “perfection,” the more it carved away at my ever more debilitated body, mind, and soul.

By the time I turned 15, I was no longer “me.” Beneath my fragile, translucent flesh lurked so much anger, so much hate, so much psychic writhing and confusion, that I was barely functional at all.

I feared everyone and everything. I feared my mother. I feared my teachers. I feared my friends. I feared food. I fear The City. I feared almost all of my greatest loves. I feared ballet. Most of all, I feared the me I had become.

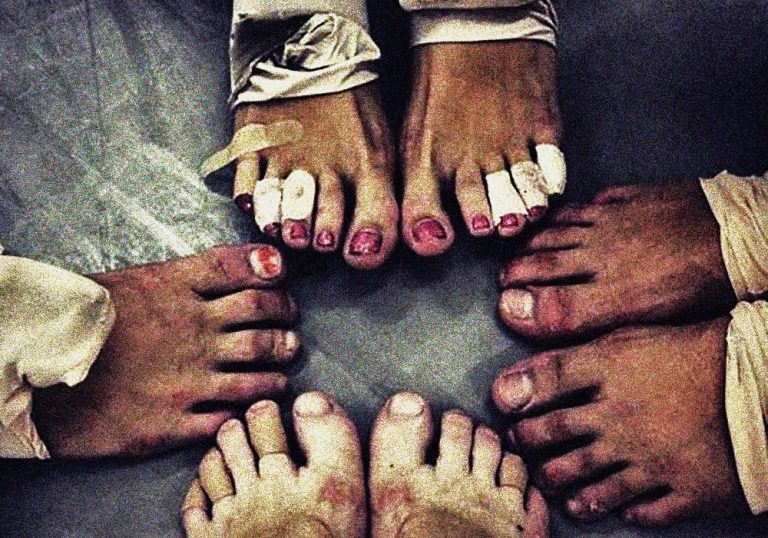

I found the most sickening form of strength in near constant self-starvation. Nearly five-foot-nine, I weighed but seventy-nine pounds. From chest pains and esophageal reflux to the stress fractures in my feet and the herniated disks, I was a broken baby bird. I was literally, seventy-nine pounds of pain.

Outside the ever-deafening pain of constant hunger, I sought release in the last and only pain I thought I could control. I started cutting. I bought Exacto® blades at Sam Flax, pretending to make an art project. I cut deeper and deeper and deeper. I wore long sleeves and tights to hide the growing Google map of scars.

For years, I thought “that spring” was supposed to be “my spring.” I was going to nail my audition for the School of American Ballet. I was going to be the belle of every gala. I was going to soar high above the throng in every fashion tent we visited, every superfabulous soiree we attended. I was going to be strong. Superstrong.

My disease had other ideas. Unable to eat for nearly 72 hours before my audition, I collapsed en pointe, just moments before I was due to appear. My ankle folded beneath me like a complicated origami crane, unleashing an excruciating, agonizing pain.

Rushed to the Hospital for Special Surgery, Mother snapped into action. It was if all of her drug-induced haze lifted like the hot, four o’clock sunshine following a cleansing mid-summer Manhattan rain.

For the first time in years, she actually nurtured me like an ultra-caring, super-comforting Trustafarian Earth Mother from an organic farm upstate. She held me close, as she took me far away to heal.

At a specialized in-patient facility, far, far away from Manhattan, she fed me coffee ice cream, one spoon at-a-time.

In sixty days at the hospital, I gained more than weight. I gained the beginnings of many understandings that I am only now coming to really know. Most of all, I learned to look inside. I learned to believe that I, ariana sexton-hughes, am more than what I wear. I am more than what my body weighs. I am more than a baby ballerina or a writer or a budding fashionista. I am smart and strong. Most of all, I am a survivor.

A few years later, the spring of senior year, after weeks of prodding by Mother, I arrived at Bryant Park. Mother was resplendent in her vintage Yves St. Laurent disco dress, black Louboutins, and exquisite, truly exquisite Fogal fishnets. I wore skinny black vintage Levis, knee-high Doc Martens, a black Badtz-Maru t-shirt, and a black 1970s Schott motorcycle jacket. We looked great. We looked really great.

We stepped out of a black car, which I insisted was a requirement of my attendance, and stepped toward the red carpet entry for VIPs. A wall of lightning accosted us, as we made our way between the velvet ropes. I buckled in silent agony, shielding my face behind Mother’s gorgeously taut, indelibly tan shoulders.

Her face turned slightly to my left ear. Mother leaned in closely and whispered ever so discretely, with more than a hint of irony, “Ariana, darling… would you prefer we leave? I am certain that Bono, Vanessa, Tyra, and Janice will more than understand.”

We both began to laugh.

“Gawd, yes. I would rather take back-to-back SATs than go through another fashion week ever again.”

Then, playing up that slight Southern drawl she uses whenever she wants you to believe that you really are the most important thing in her busy world, Mother purred softly: “Honey, we all know you would prefer back-to-back SATs to almost anything. The comparison isn’t even fair…”

I started to tear up almost immediately, as Mother wrapped her long, taut arms around my still too delicate frame and held me in an unexpectedly firm and public embrace right there on the red carpet as cameras flashed as loudly as the Macy’s Fourth of July fireworks display.

“Sebastien!” she called out to the driver. “Wait right there. Miss Ariana will be taking the car back home.”

She kissed me on the cheek, smiled for the cameras, and quickly caught up with Genevieve De La Cruz-Stein. I don’t believe she saw my smiling wave good-bye.

I never went to Fashion Week again. I didn’t want to be reminded of the me I used to be, the me I used endure. I didn’t want to fear myself. I would rather fear fashion. I didn’t want to fear the throngs. I didn’t want to fear the lights and the attention and all the faux affection. I would rather fear fashion.i